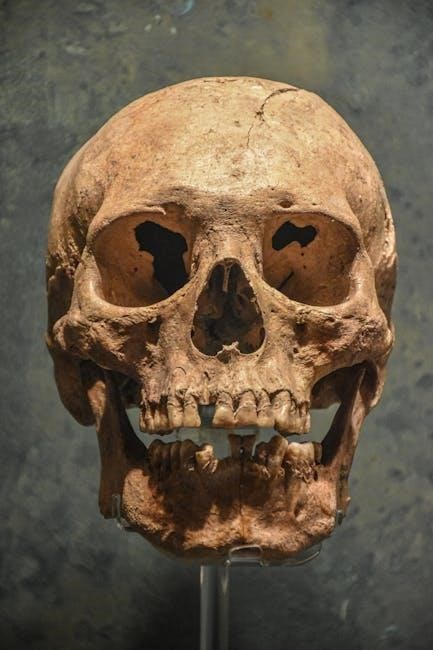

The skull, a complex skeletal structure, protects the brain, houses sensory organs, and supports facial features. Its 22 bones form a durable yet flexible framework essential for human function.

1.1 Overview of Skull Functions and Importance

The skull serves as a protective framework for the brain and sensory organs, ensuring their safety from external damage. Its complex structure supports facial features and enables essential functions like chewing, speaking, and breathing. The mandible plays a crucial role in these processes, while the cranium shields vital neurovascular structures. Understanding skull anatomy is fundamental for medical and surgical interventions, emphasizing its significance in human anatomy and clinical practices.

Structure of the Skull

The skull consists of the cranium and facial bones, forming a protective framework for the brain and sensory organs. Its structure combines strength and flexibility to support essential functions.

2.1 The Cranium

The cranium, often referred to as the braincase, is the upper part of the skull. It is composed of eight bones that fuse together to form a protective cavity for the brain. The cranium includes the frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones. These bones are connected by sutures, which provide strength and flexibility. The cranium’s primary function is to safeguard the brain, ensuring its protection from external injuries. Its structure is both robust and lightweight, allowing for optimal support and cranial capacity. The cranium also houses critical sensory organs and structures, making it a vital component of human anatomy.

2.2 Facial Bones

The facial bones form the anterior part of the skull, supporting facial structures, sensory organs, and functions like chewing and breathing. They include the maxilla, zygomatic bone, nasal bone, lacrimal bone, palatine bone, inferior nasal conchae, and mandible. These bones create the facial framework, protect sensory organs, and anchor muscles for expression and movement. Their intricate arrangement facilitates essential human functions, making them vital to both aesthetics and physiology.

Cranial Bones

The cranium consists of 8 bones: frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid. These bones form a protective framework for the brain and anchor muscles.

3.1 Frontal Bone

The frontal bone forms the anterior part of the cranium, including the forehead and upper eye orbits. It articulates with the parietal bones at the coronal suture and contains the frontal sinus; Key features include the glabella (smooth area between eyebrows) and superciliary arches, which provide attachment points for facial muscles and support the orbit’s structure.

3.2 Parietal Bones

The parietal bones form the sides and roof of the cranium, articulating at the sagittal suture along the midline. They meet the occipital bone at the lambdoid suture posteriorly and the frontal bone at the coronal suture anteriorly. These bones are essential for cranial structure, providing attachment points for muscles via their superior and inferior temporal lines, ensuring a robust and protective framework for the brain.

3.3 Temporal Bones

The temporal bones are paired bones on the skull’s sides, housing auditory and vestibular components. They contain the temporal lobe, middle ear, and inner ear, with landmarks like the external acoustic meatus and mastoid process. Articulating with the parietal bone at the squamosal suture and occipital bone at the occipitomastoid suture, they also connect with the sphenoid bone. The internal acoustic meatus transmits cranial nerves and vessels vital for hearing and balance. Fusing from separate parts by adulthood, these bones enhance cranial stability and protect neural structures.

3.4 Occipital Bone

The occipital bone forms the posterior and base of the skull, enclosing the foramen magnum, which connects the brain to the spinal cord. It articulates with the parietal and temporal bones, creating the posterior cranial fossa. Features include the external occipital protuberance and superior nuchal lines, providing attachment points for muscles. This bone is crucial for cranial protection and structural integrity, supporting the brain’s posterior region while facilitating nervous system continuity through its central foramen.

3.5 Sphenoid Bone

The sphenoid bone, located behind the nasal cavity, is a butterfly-shaped bone forming part of the cranial floor. It connects the frontal, ethmoid, and occipital bones and has two wing-like extensions. The sphenoid bone houses the sphenoidal sinuses and features key foramina, including the optic canal and superior orbital fissure, allowing passage of nerves and vessels. Its unique structure supports cranial protection and facilitates neural connections, making it vital for both cranial integrity and neurovascular function.

3.6 Ethmoid Bone

The ethmoid bone is a spongy bone located between the nasal cavity and the eye sockets, forming part of the anterior cranial floor. It contains the superior and middle nasal conchae, which project into the nasal cavity, aiding airflow and filtration. The bone also houses the ethmoidal air cells, small cavities that drain into the nasal cavity. It articulates with the frontal, sphenoid, and nasal bones, playing a key role in forming the anterior cranial fossa and supporting neurovascular structures.

Facial Bones

The facial bones form the structure of the face, supporting eyes, nose, and mouth. They include maxilla, zygomatic, nasal, lacrimal, palatine, inferior nasal conchae, and mandible, forming the orbit and facial contours.

4.1 Maxilla

The maxilla forms the upper jaw and palate, anchoring teeth and supporting the nasal cavity. It articulates with the frontal, zygomatic, and nasal bones, creating the orbital floor. Its alveolar process holds the upper teeth, while the palatine process forms the hard palate. The maxilla also contains the maxillary sinus, contributing to facial structure and respiratory function. Its complex shape facilitates multiple articulations, ensuring stability and functionality in the face.

4.2 Zygomatic Bone

The zygomatic bone forms the prominence of the cheek and contributes to the lateral wall of the orbit. It articulates with the frontal, maxilla, and temporal bones, creating a sturdy framework for facial structure. The zygomatic process forms part of the zygomatic arch, serving as an attachment point for muscles of mastication, such as the masseter. This bone is crucial for both aesthetic and functional aspects of the face, supporting orbital integrity and facial expressions.

4.3 Nasal Bone

The nasal bone forms the bridge of the nose and is part of the facial skeleton. It articulates with the frontal bone superiorly and the maxilla laterally. The nasal bone has two surfaces: the superior, which is smooth, and the lateral, which is rough for muscle attachment. It plays a key role in forming the anterior part of the nasal cavity and contributes to the anterior cranial fossa. Fractures of the nasal bone are common due to its exposed position.

4.4 Lacrimal Bone

The lacrimal bone is a thin, delicate bone located in the medial wall of the orbit. It forms part of the anterior cranial fossa and contributes to the nasal cavity. The bone features a distinctive lacrimal groove, which houses the nasolacrimal duct. This duct drains tears from the eye into the nasal cavity, making the lacrimal bone crucial for tear drainage. Its fragile structure makes it prone to fractures in facial trauma.

4.5 Palatine Bone

The palatine bone is a complex, L-shaped bone located posterior to the maxilla. It forms part of the hard palate, orbit, and nasal cavity. The bone consists of a horizontal plate and a vertical plate. The horizontal plate contributes to the posterior portion of the hard palate, while the vertical plate forms part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. It also includes the pterygoid plates, which serve as attachments for muscles of mastication. This bone is essential for separating the oral and nasal cavities.

4.6 Inferior Nasal Conchae

The inferior nasal conchae are paired, scroll-like bones projecting from the lateral walls of the nasal cavity. Unlike the superior and middle conchae, they are separate bones, not part of the ethmoid. They help humidify air and filter particles, reducing turbulence. Their curved structure enhances olfactory function and airflow. These conchae are clinically significant in nasal surgeries and contribute to respiratory efficiency, making them vital for proper nasal physiology and olfactory sensation.

4.7 Mandible

The mandible, the largest and strongest facial bone, forms the lower jaw. It consists of a horizontal body and two vertical rami. The body contains the alveolar process, housing the lower teeth, while the rami bear the condyle, coronoid, and angular processes. The mandible facilitates mastication, speech, and facial expression. It articulates with the skull via the temporomandibular joint, enabling jaw movement. The mandible also supports the floor of the mouth and anchors muscles like the tongue and mentalis, playing a vital role in both functional and aesthetic aspects of the face.

Sutures of the Skull

Sutures are fibrous joints connecting the skull bones, providing durability and flexibility. They allow for growth in younger individuals while maintaining cranial integrity and structural support.

5.1 Coronal Suture

The coronal suture is a fibrous joint connecting the frontal bone to the two parietal bones. It is located at the top of the skull and forms a serrated line that runs transversely across the cranium. This suture is crucial during infancy and early childhood, allowing the skull to expand as the brain grows. In adulthood, it typically remains visible as a distinct anatomical landmark, contributing to the skull’s structural integrity.

5.2 Sagittal Suture

The sagittal suture is a prominent fibrous joint located along the midline of the skull. It connects the two parietal bones, running from the frontal bone’s coronal suture to the occipital bone’s lambdoid suture. This suture is essential for skull flexibility during birth and early growth, allowing the parietal bones to overlap and accommodate brain expansion. In adults, it remains a visible anatomical feature, playing a key role in maintaining cranial stability and structure.

5.3 Lambdoid Suture

The lambdoid suture is located at the posterior aspect of the skull, connecting the occipital bone to the parietal bones. It is a fibrous joint with a wavy, zigzag appearance, resembling the Greek letter lambda. This suture provides structural support and flexibility, particularly during infancy, allowing for cranial expansion. It also plays a role in absorbing mechanical stresses and impacts to the skull. The lambdoid suture is an essential anatomical feature, contributing to the overall stability and integrity of the cranial structure.

Foramina and Canals

Foramina and canals in the skull are passages for nerves, blood vessels, and other structures. They facilitate communication between cranial and extracranial regions, essential for neurological and vascular functions.

6.1 Foramen Magnum

The foramen magnum is the largest opening in the skull, located in the occipital bone. It allows the spinal cord to connect with the brain, facilitating vital neurological functions. This canal is crucial for the passage of the medulla oblongata, ensuring communication between the central nervous system and the body. Its size and strategic position make it essential for maintaining bodily functions and overall nervous system integrity.

6.2 Optic Canal

The optic canal, located in the sphenoid bone, is a vital passage for the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery. It connects the orbit to the cranial cavity, enabling vision by transmitting nerve signals. Its precise alignment ensures proper visual function while protecting delicate structures. Damage to this canal can lead to vision loss, highlighting its critical role in both sensory and neurological processes.

6.3 Superior Orbital Fissure

The superior orbital fissure is a narrow passageway in the sphenoid bone, connecting the orbit to the cranial cavity. It allows crucial nerves and vessels, such as the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves, along with the ophthalmic vein, to pass through. This fissure plays a vital role in eye function and neurovascular communication, ensuring proper movement and sensation of the eye while protecting these delicate structures within the skull.

Base of the Skull

The base of the skull forms the floor of the cranial cavity, supporting the brain and connecting it to the spinal column. It features three cranial fossae and critical foramina like the foramen magnum, facilitating neurovascular communication and structural integrity.

7.1 Anterior Cranial Fossa

The anterior cranial fossa is the most anterior part of the base of the skull, housing the frontal lobe of the brain. It is formed by the frontal bone, ethmoid bone, and sphenoid bone. This fossa contains the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, which allows olfactory nerves to pass through, and the foramen cecum, a small opening for dural venous drainage. It plays a critical role in protecting the brain and facilitating sensory functions.

7.2 Middle Cranial Fossa

The middle cranial fossa is located between the anterior and posterior cranial fossae, primarily formed by the sphenoid bone and the squamous part of the temporal bone; It houses the temporal lobes of the brain and contains key foramina such as the foramen ovale and foramen spinosum. Landmarks include the sella turcica, which holds the pituitary gland, and the cavernous sinus. This fossa also accommodates the middle meningeal artery and supports neurovascular structures, playing a crucial role in brain protection and function.

7.3 Posterior Cranial Fossa

The posterior cranial fossa is the largest and deepest part of the cranial cavity, located at the base of the skull. It is primarily formed by the occipital bone, with contributions from the temporal and parietal bones. This fossa houses the cerebellum and brainstem, crucial for motor coordination and involuntary functions. Key features include the foramen magnum, through which the spinal cord connects to the brain, and the occipital condyles for articulation with the cervical spine. The posterior cranial fossa also contains the sigmoid sinuses, facilitating venous drainage.

Ontogenesis of the Skull

The skull develops through intramembranous and endochondral ossification, starting with 22 separate bones in infancy that gradually fuse, ensuring structural integrity and protection for the brain.

8.1 Development from Infancy to Adulthood

The skull develops from 22 separate bones at birth, gradually fusing through intramembranous and endochondral ossification. This process ensures proper brain protection and structural integrity. During infancy, the bones are soft and pliable, allowing for flexibility during birth. As growth progresses, sutures and fontanelles close, with full fusion typically completed by early adulthood. This adaptive process enables the skull to accommodate the expanding brain while maintaining facial proportions and functionality.

8.2 Bone Formation Processes

Skull bones form through intramembranous and endochondral ossification. Intramembranous ossification involves direct bone formation from mesenchyme, common in flat bones like the frontal and parietal. Endochondral ossification uses cartilage templates, seen in the temporal bone. Ossification centers initiate bone growth, expanding and fusing over time. This process ensures structural integrity while allowing for skull flexibility during development, particularly in early growth stages.

Clinical Significance

The skull’s clinical significance includes fractures, surgical approaches for tumors or trauma, and neurovascular structure assessments, all critical in clinical practice and neurosurgery.

9.1 Skull Fractures

Skull fractures are breaks in one or more cranial bones, often due to trauma. They can be classified as linear, depressed, comminuted, or basal fractures. Symptoms may include pain, swelling, or neurological deficits. Diagnosis involves imaging techniques like CT scans. Treatment varies from conservative management to surgical intervention, depending on fracture severity and associated complications. Prompt medical attention is critical to prevent infections or brain damage, ensuring proper healing and functional recovery.

9.2 Surgical Approaches

Surgical approaches to the skull are tailored to address specific conditions, such as fractures, tumors, or vascular anomalies. Techniques include craniotomy (removing a bone flap) for access to the brain or endoscopic methods for minimally invasive procedures. Surgeons consider anatomical landmarks, such as sutures and foramina, to minimize tissue damage. Reconstruction often involves reattaching bone fragments or using prosthetics to restore structural integrity and function. Precision and expertise are critical in these complex procedures to ensure optimal outcomes.

9.3 Neurovascular Structures

The skull houses critical neurovascular structures, including major blood vessels and nerves. The internal carotid artery enters through the carotid canal, supplying blood to the brain. The optic nerve passes through the optic canal, enabling vision. Cranial nerves exit via specific foramina, such as the jugular foramen, to innervate vital functions. These structures are protected by bony canals and foramina, ensuring their integrity while maintaining brain function and sensory capabilities. Damage to these structures can lead to severe neurological deficits.